For Swimmers: The Complete Guide to Jellyfish

How to identify poisonous jellyfish and prevent and treat their stings

By Simon Lockwood, Expert Reviewer for Repellent Guide

published: Apr 23, 2017 | updated: Aug 01, 2017

Many people share the common misconception that all gelatinous floating sea creatures are jellyfish and that all of these creatures are capable of producing very painful (or even deadly) stings, when neither of these myths are true. In reality, only a handful of jellyfish species frequently come into contact with swimmers, and many of these produce fairly mild stings. As such, you should not let fear of jellyfish prevent you from enjoying the water; with a bit of education regarding jellyfish types and sting prevention and management, you should be able to share the shores with this fascinating, ancient creature without incident.

Types of Poisonous Jellyfish Commonly Encountered by Swimmers

While there are many kinds of jellyfish filling the world's oceans, many of them will never come into contact with humans. The following types of poisonous jellyfish are, however, known to enter shallow water, and swimmers often encounter them along beaches.

Note that while many of the jellyfish species not on the list below cause only “mild” stings or no stings at all, experts still advise beach-goers to avoid touching them if at all possible, as some individuals are more sensitive to jellyfish stings than others, so a noticeable reaction is always possible. Likewise, it's easy to harm jellyfish accidentally when handling them, or to mistake a poisonous jellyfish for a harmless variety.

Cotylorhiza tuberculata

This jellyfish, which is very abundant throughout the Mediterranean, causes mild but irritating stings in sensitive individuals. It enjoys the warm, shallow water of bays, particularly around Italy, and is known for being extremely beautiful. This jellyfish is about 30 cm in diameter on average and the manubrium (area under the umbrella) of this species is said to resemble a bouquet of flowers owing to the blue “dots” on the end of its tentacles.

This jellyfish, which is very abundant throughout the Mediterranean, causes mild but irritating stings in sensitive individuals. It enjoys the warm, shallow water of bays, particularly around Italy, and is known for being extremely beautiful. This jellyfish is about 30 cm in diameter on average and the manubrium (area under the umbrella) of this species is said to resemble a bouquet of flowers owing to the blue “dots” on the end of its tentacles. Carybdea marsupialis

As this species is a “cubozoan,” a relative of the deadly jellyfishes that dwell along the coasts of Australia, swimmers entering its native habitat (the shores of Italy) should be careful: Though marsupialis stings are not fatal, they can be very painful. Be sure to watch out for small (just 4-5 cm) jellyfish with cubic umbrellas and 4 long tentacles which swim quickly and are attracted to light. This species is known to be a common source of stings as it is small, fast, and easy to overlook.

As this species is a “cubozoan,” a relative of the deadly jellyfishes that dwell along the coasts of Australia, swimmers entering its native habitat (the shores of Italy) should be careful: Though marsupialis stings are not fatal, they can be very painful. Be sure to watch out for small (just 4-5 cm) jellyfish with cubic umbrellas and 4 long tentacles which swim quickly and are attracted to light. This species is known to be a common source of stings as it is small, fast, and easy to overlook.Cassiopea andromeda

While not very dangerous, this jellyfish produces a mucus which is quite irritating to human skin. This jellyfish, which is frequently found around the coasts of Turkey, Italy, and Malta, is easily identified owing to the fact that it appears to swim “upside down” (tentacles facing upward, mouth on the bottom).

While not very dangerous, this jellyfish produces a mucus which is quite irritating to human skin. This jellyfish, which is frequently found around the coasts of Turkey, Italy, and Malta, is easily identified owing to the fact that it appears to swim “upside down” (tentacles facing upward, mouth on the bottom). Rhizostoma Pulmo

This very large (60 cm in diameter) white and blue Mediterranean jellyfish causes mild but irritating rash-inducing stings. It can be easily identified by its large size and “cauliflower” shaped manubrium.

This very large (60 cm in diameter) white and blue Mediterranean jellyfish causes mild but irritating rash-inducing stings. It can be easily identified by its large size and “cauliflower” shaped manubrium.Rhopilema nomadica

This jellyfish is not only a very painful stinger, it's often confused with the nearly-harmless Rhizostoma; however, it lacks Rhizostoma's characteristic blue rim, a difference which swimmers should be vigilant for. Found throughout the Indo-Pacific ocean, the species has now migrated through the Suez canal, reaching Israeli coasts and causing alarm along many beaches in the eastern Mediterranean. It is very large (80 cm in diameter) and often forms large swarms.

North American Chrysaora

Referred to as the “Sea Nettle”, this jellyfish is common on both coasts of North America and produces painful stings. This 30 cm-wide jellyfish can be identified by its many tentacles (24) which attain lengths of over 6 feet.

Referred to as the “Sea Nettle”, this jellyfish is common on both coasts of North America and produces painful stings. This 30 cm-wide jellyfish can be identified by its many tentacles (24) which attain lengths of over 6 feet.Cyanea capillata

There is no missing the Cyanea capillata (aka the “Lion's Mane” jellyfish); this massive species can grow to measure 8 feet in diameter and have tentacles which trail over 100 feet. Though the Lion's Mane jellyfish is found throughout colder waters in the Atlantic, it usually only encounters humans off the coast of Australia, where it may cause very painful (and more rarely, fatal) stings. Though this jellyfish is fairly easily sighted and avoided, its tentacles can pose a hazard even after the animal has died and they have dispersed.

There is no missing the Cyanea capillata (aka the “Lion's Mane” jellyfish); this massive species can grow to measure 8 feet in diameter and have tentacles which trail over 100 feet. Though the Lion's Mane jellyfish is found throughout colder waters in the Atlantic, it usually only encounters humans off the coast of Australia, where it may cause very painful (and more rarely, fatal) stings. Though this jellyfish is fairly easily sighted and avoided, its tentacles can pose a hazard even after the animal has died and they have dispersed.Physalia physalis

The infamous Man O' War, while not a true jellyfish, should be mentioned on any list of poisonous jellyfish as it is a frequent and very dangerous stinger. Named for its shape (it resembles the sail shape of a 17th century naval vessel), this striking blue creature has a very wide range throughout the Atlantic, but like the Lion's Mane, it usually encounters swimmers around Australia, where it causes 10,000 stings per year. Its venom is far more toxic than many “true” jellyfish, and where most jellyfish have stings whose effects last only hours, the Man O' War can cause severe lasting illness which may send the sufferer's body into shock, leading to death.

The infamous Man O' War, while not a true jellyfish, should be mentioned on any list of poisonous jellyfish as it is a frequent and very dangerous stinger. Named for its shape (it resembles the sail shape of a 17th century naval vessel), this striking blue creature has a very wide range throughout the Atlantic, but like the Lion's Mane, it usually encounters swimmers around Australia, where it causes 10,000 stings per year. Its venom is far more toxic than many “true” jellyfish, and where most jellyfish have stings whose effects last only hours, the Man O' War can cause severe lasting illness which may send the sufferer's body into shock, leading to death.Chironex fleckeri

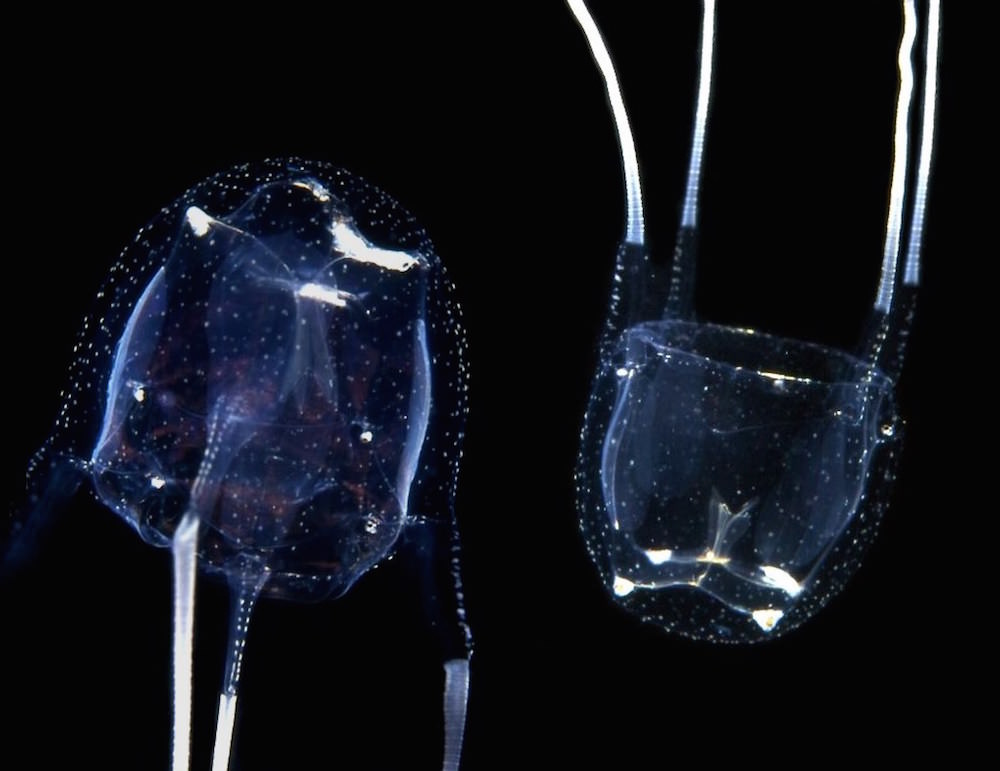

The “Box Jellyfish”, another species which congregates primarily around Australia, is the most dangerous “true” jellyfish in existence, having been responsible for at least 5,568 deaths recorded since 1954. The venom of fleckeri, the largest species of Box Jellyfish (identifiable by its box-like shape, clear umbrella, and 15 tentacles which may grow up to 10 feet in length), can kill within minutes, and even tiny species within the Box Jellyfish family (e.g. Carukia barnesi) can cause very painful, sometimes dangerous stings. In general, if a swimmer encounters a jellyfish which is boxy in appearance, he or she should leave the water immediately.

The “Box Jellyfish”, another species which congregates primarily around Australia, is the most dangerous “true” jellyfish in existence, having been responsible for at least 5,568 deaths recorded since 1954. The venom of fleckeri, the largest species of Box Jellyfish (identifiable by its box-like shape, clear umbrella, and 15 tentacles which may grow up to 10 feet in length), can kill within minutes, and even tiny species within the Box Jellyfish family (e.g. Carukia barnesi) can cause very painful, sometimes dangerous stings. In general, if a swimmer encounters a jellyfish which is boxy in appearance, he or she should leave the water immediately.

Tips For Preventing Jellyfish Stings

As jellyfish in some areas can be very dangerous, it's considered wise to try to prevent getting stung rather than trying to treat stings after they happen.

Some tips for avoiding jellyfish stings include:

Look for signs which warn about jellyfish-infested waters. Often beaches and bays where jellyfish congregate have posted warning signs, or purple flags (which signify hazardous marine life in many countries), making people aware of the danger. If you're unsure of whether or not jellyfish inhabit a given beach, ask the lifeguard on duty if there has been jellyfish activity in the area recently. You should also leave the water if you spot a jellyfish and do not enter the water again until you have verified that it is not a dangerous variety.

Keep an eye out for anything that looks like a floating tentacle. As mentioned above, some species of jellyfish have tentacles which can sting even after the animal has died and they have detached from it and floated away. In fact, the dispersed tentacles from a single deceased Lion's Mane jellyfish once stung an estimated 150 people swimming in New Hampshire (USA). Swimmers should therefore remain vigilant when swimming and leave the water if they sight anything which resembles a jellyfish tentacle, particularly if they are swimming in a region where highly dangerous species of jellyfish are found. Likewise, never touch a dead jellyfish that has washed up on shore.

Avoid the beach when jellyfish-attracting weather conditions are present. Jellyfish often wind up on the beach after periods of heavy rain or high winds, and they are also known to come closer to shore after periods of warmer weather. Note that some regions also experience a “jellyfish season” (e.g. Box Jellyfish are far more dense in Australian waters during the wet season which spans from October to May) where the animals become far more common; if you're travelling, research when jellyfish season occurs and try to plan your trip at a different time.

Wear jellyfish repellant. Today, jellyfish repellant is widely available; in fact, there are now some brands of repellant which double as sunscreen. These lotions are PABA-free and non-comedogenic and protect against even Box Jellyfish and Sea Nettles through fooling the creatures into thinking the swimmer is another jellyfish (so they do not react with alarm and sting). Additionally, in the event that mechanism fails, the lotion also includes an extract of plankton which is proven to help block a jellyfish's sting sensor so that it cannot send the “sting” message to the jellyfish's brain. As some poisonous types of jellyfish are very small, and thus easily contacted by accident, it is strongly advised that all swimmers entering jellyfish habitats apply jellyfish repellant.

What to Do if You Get Stung By a Jellyfish

As you may not realize you have been stung by a jellyfish owing to the tiny size of some species and the risk posed by floating tentacle pieces, it's important to learn to identify the symptoms of a jellyfish sting. These include:

- A burning, prickling or stinging pain. This may occur suddenly or several hours after you have left the water, depending on the type of jellyfish which stung you.

- Tracks on the skin (often red, brown or purple) which reflect the imprints of tentacles in shape.

- Itching

- Swelling

- Tingling or numbness.

If you notice any of the above symptoms, check the water around you and take note of the appearance of the jellyfish which stung you so that you can describe it to a medical professional. Immediately notify the lifeguard on duty that you have been stung and attempt to identify whether or not you're in danger of serious illness. If you have been stung by a very toxic species, the lifeguard should be able to perform CPR if needed and keep you stable until help arrives.

If it is established that your sting is not dangerous, you should:

Rinse the area repeatedly with salt water. Never use fresh water (e.g. from a water bottle) to rinse the sting as it can actually cause the tentacle to break down, spreading the stingers within it over a wider area. You should also be sure to avoid getting sand in the wounds, and never rub them with a towel. If you only realize you have been stung after you have left the beach, either purchase a saline solution to rinse it or use vinegar.

Treat the sting by soaking it. If your wound continues to hurt over the coming days, try soaking it in warm water with Epsom salt added to it. The combination of water and salt actually helps to remove venom from the sting site, shortening the duration of symptoms. Avoid “folk remedies” like applying alcohol or urine to the area—both of these will only cause further irritation.

Try an over-the-counter remedy. Oral antihistamines and steroidal anti-inflammatory creams can both help to counteract the venom of jellyfish stings and quell the body's reactions to the toxin. Be aware, however, that other common remedies for plant and insect stings, like lidocaine or calamine lotion, don't tend to be particularly effective for treating jellyfish stings. Rather than applying such lotions, it's better to place your focus on keeping the wound clean and covered in order to mitigate any risk of infection and facilitate healing.

As is the case with any injury, if you have been stung by a jellyfish, you should remain vigilant for signs of serious illness; if the pain from your sting worsens significantly or suddenly, or if you begin to run a fever, feel weak or dizzy, or have a rapid heartbeat, seek medical attention immediately. Also, be aware that if you have been stung by a Man O' War, even if you survive the initial sting, it's common to experience symptoms of illness for many months after the pain of the initial wound is gone. Talk to your healthcare provider in order to come up with a plan for symptom management.

As a final note, it's important to remember that while jellyfish stings should be taken seriously, many healthy people survive contact with even the most dangerous of species, so if you get stung, there's no need to panic—simply take the precautions outlined above. Elderly people, children, and those with existing medical conditions (asthma, diabetes, autoimmune conditions, etc.) comprise many of the recorded jellyfish-related fatalities, and should practice extra caution while in the water.

-

Gel

-

Lotion